Founding

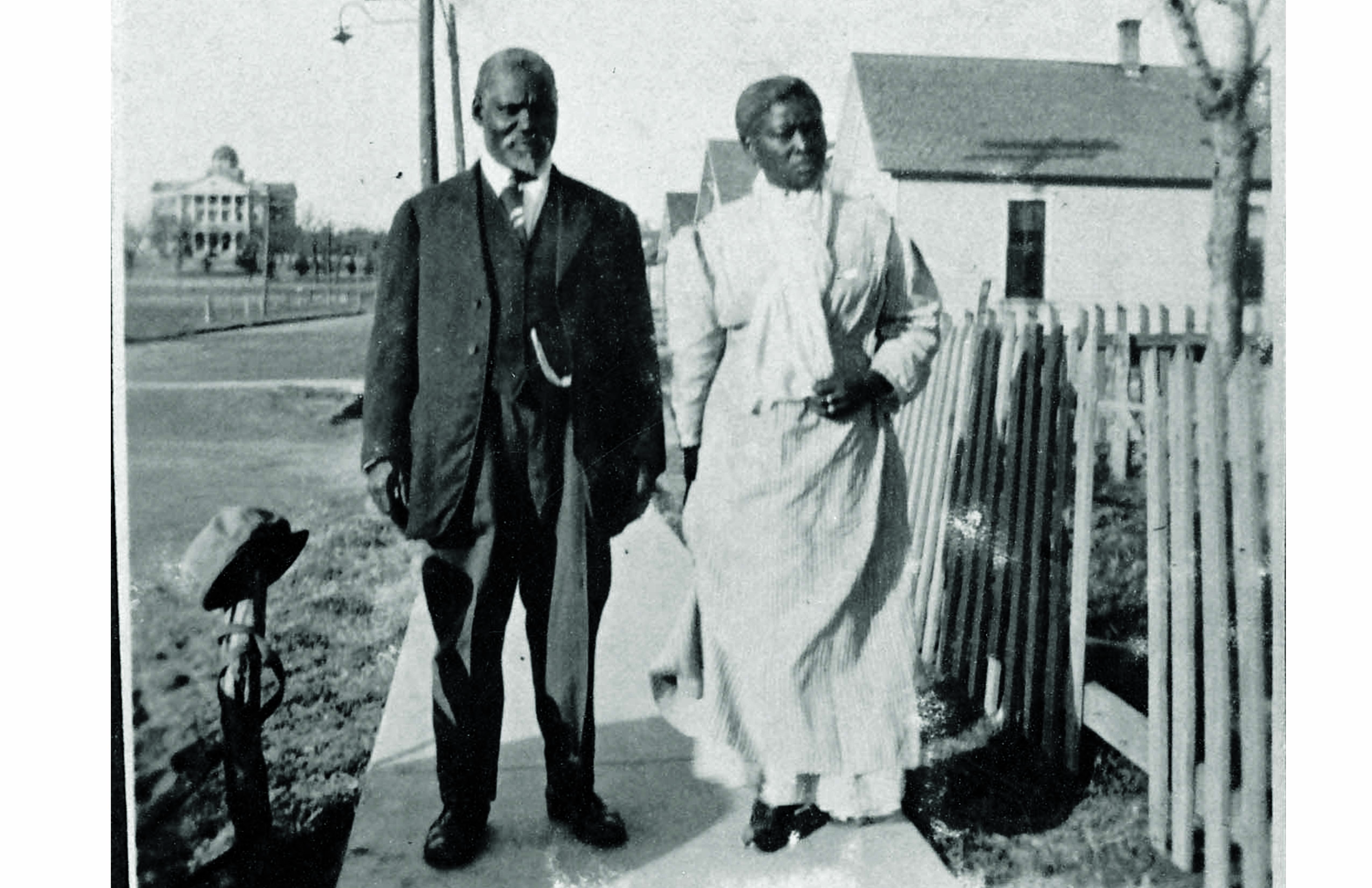

In 1875, a group of twenty-seven black families left the Dallas area seeking new opportunities outside of life on the plantation. They settled in Denton and called their new community Freedman Town. In the same year, members of the community formed a congregation for religious worship that would become St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The original charter members of the church were Jim Crawford, Dicy Crawford, Jerry Crawford, Ford Crawford, Jim Hall, Phyllis Hall, Giles Lawson, Ester Lawson, Arthur Cochram, Harriet Cochram, L.T. Lambert, Sallie Lambert, Henry Maddox, Charlotte Maddox, Jim Holt, Mattie Hold, Emly Russell, and C.R. Hembry. In the earliest years of the organization’s existence the congregation met in each others’ private homes. For the first year, Rev. L.T. Lambert lead the congregation as the St. James A.M.E. Church’s only minister at the time. In the following year, 1876, Rev. J.V.B. Goins became the new church’s pastor.

Building a Community

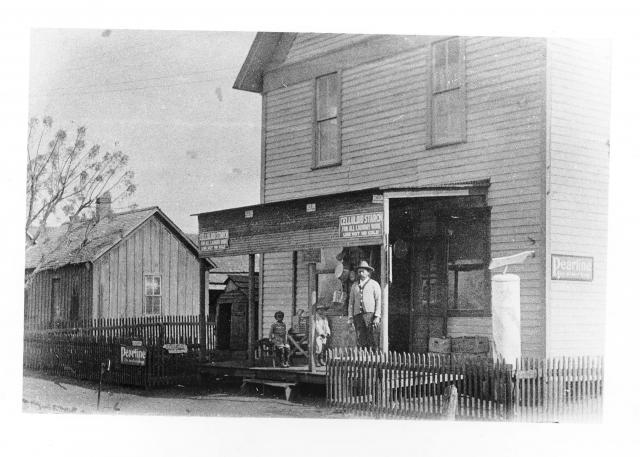

By 1880, most black residents now resided in a community called Quakertown. With the community becoming more established, the need for a church building was clear. In 1882, documents were submitted to reserve land to build a church building. Henry and Charlotte Maddox helped organize a group to plan and build the church. They collected the wood for church building themselves. The St. James A.M.E. Church became the first church in Quakertown.

In the early 1890s, the church was moved to Oakland Ave and the congregation’s leadership was transferred to Rev. D. Hill. In addition to the church being moved, a second smaller building was also erected. In 1899, Rev. J.S. Powe took leadership of the St. James A.M.E. Church. In this same year the church was rebuilt. A decade later in 1909, another building was built under Rev. A.J. Cooper.

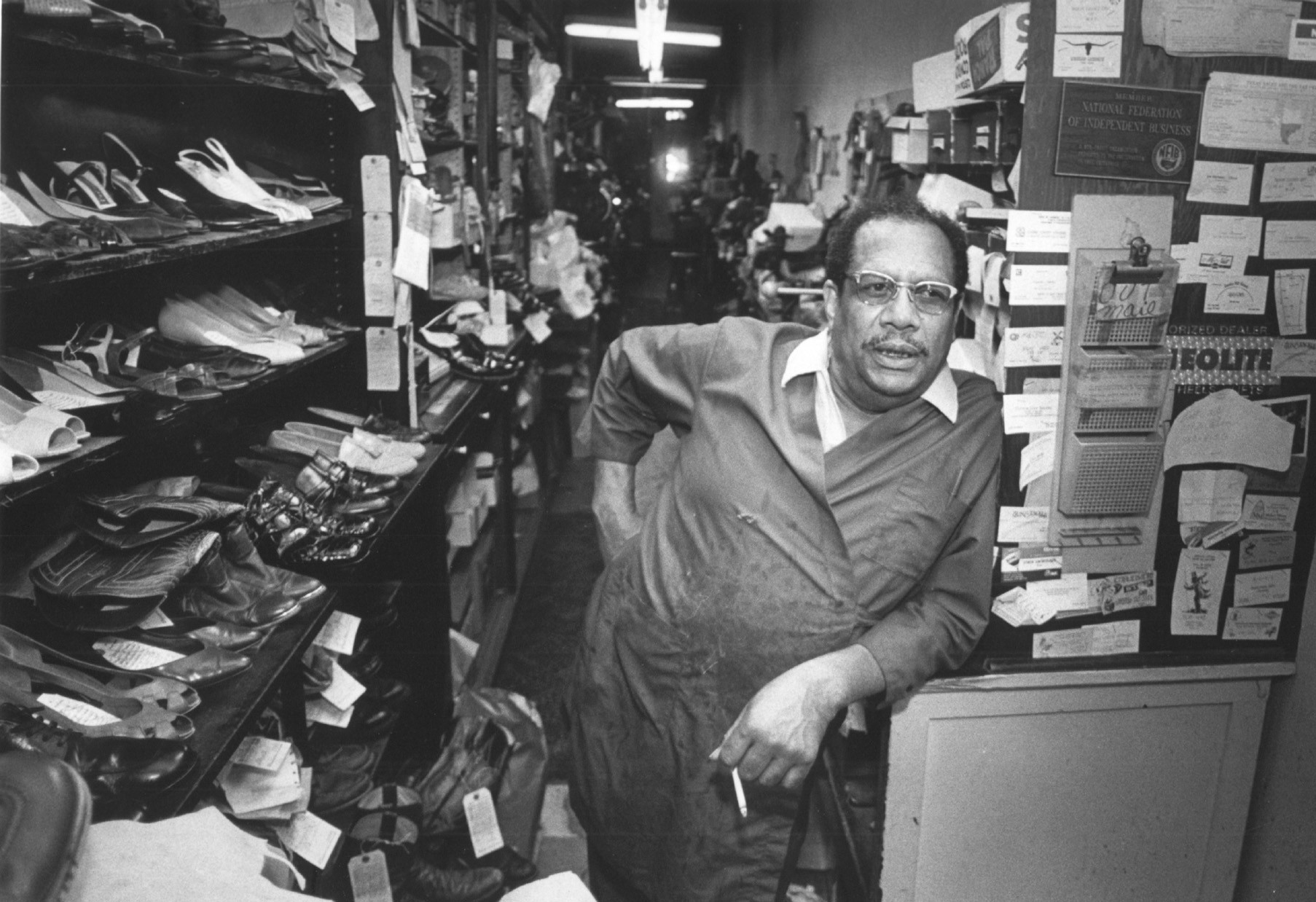

In 1913, The only all-black school in Denton, the Frederick Douglass School, burned down. With no where else to go, classes were held in the basement of the St. James A.M.E. Church until the new school was built in the southeast side of Denton. In addition to temporarily housing the school, the church was involved in hosting various events and conferences. They hosted concerts and workshops and talks from prominent academic figures. In 1921, the church hosted the 15th Annual Session of the Texas Negro Business League. Black business men from all over the state attended the event to learn how to succeed in business, how to obtain their civil rights on a federal level, the importance of solidarity, the importance of fire insurance, and other important talks.

Displacement

In 1921, the City of Denton began purchasing lots from Quakertown residents with the intention of removing the community and building a park. The church’s plot of land was purchased by the city in 1922. Many Quakertown residents, like the Hill family, were able to move their houses to Solomon Hill. However, this wasn’t possible for the St. James A.M.E. Church. The building was wrecked and a new building was constructed on the corner of Oak and Crawford Streets. This location continues to serve as the church’s home.

Change and Growth for St. James A.M.E.

Through the 20th century, the church went through continued changes in leadership and updates to the church. Due to the age of the building, in 1962 the lot was cleared to construct a newer brick building. The church continued to modernize and was occasionally the Denton Christian Women’s Interracial Fellowship used the building for their meetings. The St. James A.M.E. Church welcomed its first female pastor, Rev. Robbie L. Slaughter in 1980. In 1985, during Rev. Slaughter’s time leading the church, they received a state historical marker on their 110th anniversary.

In 2021, it was discovered that the roof was sagging. Upon closer inspection they found out that the rafters were broken as well as the trusses, resulting in the roof needing to be replaced. The church was able to obtain a loan for $50,000 to help with repairs. A crowdsourcing campaign was set up to help them pay off the loan.

Sources Used:

1882 Land Documents for the A.M.E. Church. Document Copy, Denton, TX, 1882. Donated to the Denton County Office of History and Culture by Michele Glaze.

Breeding, Lucinda. “Sharing the Load: Partners Join Forces to Save Denton’s Oldest Black Church.” Denton Record-Chronicle. April 30, 2021. Found Here.

“The Frederick Douglass School.” Denton County Office of History and

“Interracial Meet Here Tuesday.” Denton Record-Chronicle 42, No. 138 (Denton, TX), January 22, 1945. p. 3. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

“Make the Business League a Success.” The Dallas Express 28, No. 39 (Dallas, TX), July 2, 1921. p. 4. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

McAdams, Willie Frances. “Saint James African Methodist Episcopal Church.” Research paper, Denton, TX, 1983. Found Here .

Moten, Edwin D. Letter to L.T. Lambert. Letter, Indianapolis, IN, 1943. Donated to the Denton County Office of History and Culture by the Historic Park Foundation of Denton County. It can also be found on the Portal to Texas History.

“Negro Educator Here.” Denton Record-Chronicle 16, No. 169 (Denton, TX), February 28, 1916. p. 6. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

“Negroes to Sing Folk Songs Here.” Denton Record-Chronicle 28, No. 51 (Denton, TX,) October 12, 1928. p. 6. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

“Prof. Kelly Miller, A.M.LL.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Howard University, Washington, D.C., Will Lecture.” Denton Record-Chronicle 19, No. 272 (Denton, TX), June 26, 1919. p. 5. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

“St. James A.M.E. Church: 125th Church Anniversary.” Pamphlet, Denton, TX, 1996. Donated to the Denton County Office of History and Culture by Kemp Caraway.

“State Business League Will Open Monday at St. James.” The Dallas Express 28, No. 39 (Dallas, TX), July 2, 1921. p.3. Found on the Portal to Texas History.

Woo, Jeff. Photo of the St. James A.M.E. Church. April 30, 2021. Found Here.