The late sixties, especially the year of 1969, were a time of juxtaposition – an era equally defined by peace and love, as well as war and conflict. Among the juxtapositions of the sixties stood one event, taking place Labor Day Weekend 1969 in a small, quiet farm town 12 miles north of Dallas. The Texas International Pop Festival, which took place a mere two weeks after Woodstock, shook Lewisville, Texas, bringing in over 120,000 hippies and a handful of internationally acclaimed artists.

Lewisville in 1969 was no flower-child haven. Nestled along I-35E, it was no more than a mere pit stop for those traveling from Dallas to Oklahoma. The population of 8,000 had deep roots in farming and was more suited for a cowboy than anyone interested in the era’s counterculture. Before the festival, the largest events Lewisville witnessed were rodeos and high school football games. Such an event would have seemed more fitting in a metropolitan area like Dallas or Austin. However, the open space and cool lake made it the perfect location to celebrate peace, love, and music.

Pop Fest Comes to Texas

So how exactly did such an event land in Texas? Though hippie culture could be found across the states, the hubs thrived in California and New York. Texas, on the other hand, wasn’t nearly as embracing.

The endeavor began with a 25-year old man named Angus Wynne III, son of a wealthy North Texas family. His father, Angus Wynne Jr., founded Six Flags Over Texas in Arlington and Grapevine’s Great Industrial District. Wynne III, who had been working with the Dallas-based concert promotion company, Showco, attended the Atlanta Pop Fest on July 4th weekend, 1969. The event inspired him to set up his own version of the festivities. Soon, Wynne found himself partnered with the promoter for the Atlanta Pop Fest, Jack Calmes, and Alex Cooley, who worked with Interpop Superfest, another concert promotion company. Together, the three planned to bring the pop fest scene to Texas.

Planning immediately went underway. The date was officially set for Labor Day weekend, giving the trio only a month and a half to prepare for a mass event. Dallas-based advertisers, SL Associates, were hired to handle publicity and media coverage. All the while, the promoters went to work finding bands.

Cooley, who had organized Atlanta Pop Fest, roped in nine of the big names who performed at his previous festival. Wynne, who was a rhythm and blues fan, scouted for artists of his preferred genre. This made for one of the biggest differences between Woodstock and the Texas Pop Fest. While New York showcased an array of folk artists, Lewisville would be bringing the blues to their festival. With a budget of $120,000, the promoters were able to book 26 bands, some of which who were internationally acclaimed. Their highest paid acts were set to receive $10,000 for playing the festival, which was ultimately a low paycheck.

When the planning began, there was no official venue set. The affair was set to take place in North Texas, but there was no telling which town it would land in. However, it didn’t take long for Wynne to find their location. On the southern end of Lewisville along I-35 stood the Dallas International Motor Speedway, which had opened earlier that summer. With its close proximity to Dallas, easy highway access, and large offset pastures, Lewisville was their ideal location. Contracts were made and soon the Texas Pop Fest had a home. However, having a three-day festival made finding overnight accommodations necessary. Wynne soon partnered with a local public campground just north of Lake Lewisville to serve as the home base for festival goers. Additionally, arrangements were made to set up a “Free Stage” at the campgrounds for local bands to play.

Woodstock, Security, and Controversy

Former Lewisville police chief, Ralph Adams, discusses his resignation and the Texas International Pop Festival on television.

Woodstock, the hippie gathering of the century, took place two weeks before Texas International Pop Fest, so Angus Wynne took it upon himself to go study it. Flying to New York in his father’s private jet, Wynne headed out to Yasgur’s Farm, joining the crowd of over 400,000.

One of the biggest issues he saw with Woodstock was the lack of a fence. Crowds arrived before perimeters could be established, leading to the festival’s over-attendance. Thousands upon thousands entered for free – an issue that Wynne was able to resolve at his own event.

The festivals of the sixties were often void of police security. Promoters knew if uniformed law enforcement patrolled their events, there would be a high risk of cultural clash. Therefore, they often turned to biker gangs or communes for security. In the case of Woodstock, New Mexico’s Hog Farm commune kept things calm with their “Please Force”. They stated that their tactics were a non-intrusive form of keeping the peace by asking attendants to “please do this” or “please don’t do that”. Additionally, the famous Merry Pranksters commune, led by Ken Kesey, did their part to keep festival goers in order. When food was scarce, they supplied the masses with free meals. Impressed by their work, Wynne hired both communes to work the Texas Pop Festival.

However, Wynne knew the lax form of security would not be enough to satisfy locals, which led him to reach out to Lewisville Police Chief, Ralph Adams. Adams, who was soon to resign, agreed to serve as head of security for the festival and the two made a deal that no uniformed officers would enter the grounds. With police at bay, festival promoters believed the chances of conflict would decrease. However, the chief’s decision to partner with the event was deeply unsettling for the community.

Soon, criticism was coming from every direction. City government officials began speaking out against the event and Lewisville’s mayor, Sam Houston, was called upon to cancel the ordeal. Adams soon received criticism from the Dallas County District Attorney, Henry Wade, and Assistant US Attorney General, Will Wilson. Local newspapers published editorials against the festival and Mayor Houston spoke with an attorney to find a way to stop the event. Unfortunately for them, it was too late in the planning process to take any legal action. Meanwhile, newspapers continued advocating against the festival, publishing Woodstock horror stories that encouraged parents to keep their children as far away from Dallas International Motor Speedway as possible. Mayor Houston purchased a pistol and prepared for the worst.

The Show Begins

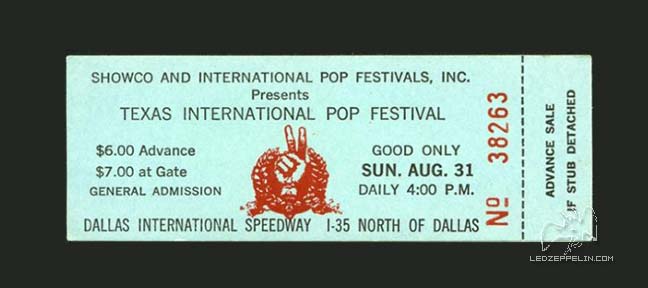

A ticket to the Texas International Pop Festival.

Despite negative press and an outcry against the Texas International Pop Festival, Wynne and Cooley moved forward. They paid newspapers and radio stations across Texas to promote the show and the excitement quickly spread. Radio stations held contests for free tickets. One contest asked listeners to send in the most uniquely decorated rock, a nod to the rock and roll they’d be listening to at the festival. Publicity articles were also planted that warned attendees of counterfeit tickets. Ultimately, festival promotions attracted music-lovers from across Texas, the United States, and even other countries. More than 120,000 tickets were sold at a cost of $6.00 to $7.00 per day.

Labor Day Weekend approached, bringing thousands upon thousands into town – more people than Lewisville had ever witnessed. The majority of the crowd piled in for the 30-act, 3-day concert, though some arrived, ironically enough, for a rodeo that was taking place in town the same weekend. The festival kicked off with an unknown band from Michigan, Grand Funk Railroad. They were not originally chosen for the lineup, but Wynne and the band’s manager made a deal, because any exposure is better than none at all. Wynne allowed the band to open the festival each day, but they played for free and had to fund their own travel and meal expenses.

The festival grounds were essentially a hippie carnival. Vendor booths included astrologers, painters, and leather crafters. Other stands sold incense, t-shirts, bangles, beads, and candles. The Hog Farm commune provided free food to festival goers and watched over the event, while the Merry Pranksters tended to the campgrounds. A brotherly spirit ensued among the crowd – everyone shared, no one fought, and all sought a peaceful, good time.

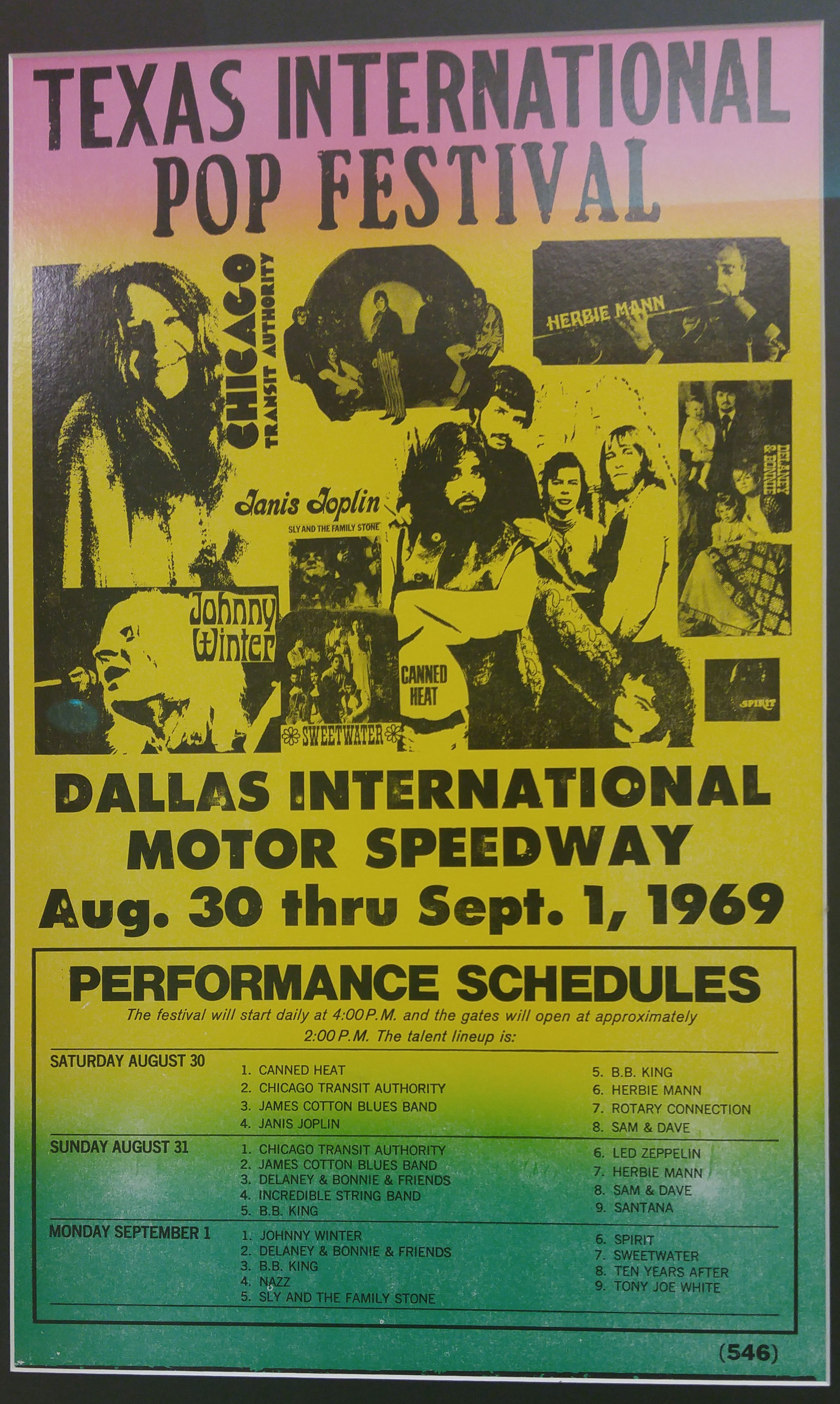

Performance schedule poster for the Texas International Pop Festival.

With the festival’s top-notch line up, it was hard not to feel elated. Blues artists of the weekend included B.B. King, Johnny Winter, James Cotton Blues Band, Canned Heat, Delaney and Bonnie, and Freddie King. Performances by Sly & the Family Stone and Sam & Dave highlighted rhythm and blues. Janis Joplin, Led Zeppelin, Santana, Rotary Connection, Ten Years After, Chicago Transit Authority, Nazz, Spirit, and Sweetwater gave the crowds electrifying rock and roll. Herbie Mann highlighted jazz, while Tony Joe White provided a taste of Cajun. Crosby, Stills, & Nash were originally billed to play, but cancelled after feeling less than satisfied with their Woodstock performance. They instead went back to rehearsals.

A few of the big name acts hailed from Texas. Johnny Winter was a Beaumont native; Freddie King’s roots came from Gilmore; Sly Stone was born in Denton and still has family here today. The most notorious was probably Janis Joplin who grew up in Port Arthur and attended the University of Texas in Austin before leaving the state. Having never fit in, she left Texas with an ill will. However, the identity she found in San Francisco skyrocketed her career. Janis closed out the first night of the festival, her band playing well past 3 a.m. It was her first time returning to Texas since leaving for California. Though she was happy to receive a warm welcome, Joplin asked the crowd mid-set, “where were you when I needed you?”

Janis Joplin, Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin, and Santana performing at the Texas International Pop Fest.

The free stage, set up at the adjacent campgrounds, hosted a number of local bands. Shiva Shiva and Ramon Ramon & The Four Daddios traveled from Austin to play. However, some bigger names played at the campgrounds simply for the fun of it. One evening, Hugh Romney of the Hog Farm and a friend were laying on the free stage playing with silly phrases such as “mumbly wumbly” and “wavy gravy.” B.B. King approached at that moment and addressed Romney as “Wavy Gravy”, a name that stuck. King and Johnny Winter then proceeded to play the stage for hours. Wavy Gravy has since become a counterculture icon and had a Ben and Jerry’s ice cream flavor named in his honor.

Expecting the worst

Among the many worries of hosting the festival in Lewisville was the possibility of hippies wreaking drug-fueled havoc across town. Though police were not permitted inside the gates, legal action was still taken by making arrests outside and towing cars parked along the interstate. However, things remained generally peaceful both inside the festival and through the town. One Lewisville native recalled a story of seeing a group of hippies walking down her street. Unsettled, she ushered her children inside immediately. When one of the men knocked on her door, she was initially frightened but was soon relieved when he simply offered to mow her lawn. He asked for no money, but a just a bit of food in return. A number of community members ended their weekend with at least one positive interaction with the counterculture youth.

Additionally, large teams of medics were hired to work onsite at the festival. They prepared themselves for the worst, expecting to face many cases of drug abuse throughout the weekend. However, the issue was minuscule. Most of their time and attention was focused on bandaging cut feet or helping with heat-related illnesses. Unfortunately, one man from Arlington, Texas suffered a heat stroke at the festival and later died in a Dallas hospital.

Out of all of the worst issues expected, very few came to fruition. Out of 120,000 attendees, only 80 arrests were made, a mere 25 of which were drug related. Very few attendees were able to scale the fence successfully, so free admission became a non-issue. No instances of violence ever arose, which many attribute to the ban of liquor sales at the festival site (though it can’t be denied that marijuana and LSD were both present). The setting was peaceful, and the problems were few. At the end of the festival, both Adams and Houston spoke on stage commending the concert goers on their behavior.

Skinny Dipping

One issue was overlooked at the campgrounds. The public sites were void of showers, which led overnight concertgoers to bathe in the lake. Passing bars of ivory soap around, the uninhibited crowds waded through the water in the nude. The skinny dipping caused an uproar with locals, and endless calls flooded police phone lines. The Mayor held an impromptu midnight meeting with Houston, Wynne, and Adams, demanding an end to the nudity. The next day, Wavy Gravy pleaded with the nudists but to no avail.

Ironically, the skinny dipping seemed to be as fascinating as it was disgusting to Lewisville natives. Men crowded onto boats, sailing close to the shore in order to watch the bathers. An older couple near the lake called the act “disgusting”, though they spent hours watching the nude crowd with binoculars. Two elderly women walked a mile and a half to go catch a peek as well.

Success or Failure?

It is hard to say whether the Texas International Pop Festival was a success or failure. In fact, it probably would come down to who you asked. Ultimately, it was a financial failure, losing almost $100,000 which left the promoters a huge debt to pay. Lawsuits also arose in the following years, a headache all on their own. However, many concert goers would say it was a success. On many accounts, attendees have remembered it as one of the best times of their lives – a weekend abound with peace, love, and ultimately, good music.

However, Mayor Houston claimed the festival was terrible for the city and local businesses. Though he commended the concert goers, he promised the townspeople that an event like the festival would never happen again. He later stated that he wished the Texas Pop Fest never occurred. The press also had a heyday with the festival. The Dallas Morning News published a scathing article titled “Nausea at Lewisville” which read, “young people assembling to hear music is one thing. Young people assembling in unspeakable costumes, half-naked, bare-footed, defying propriety and scorning morality is another.”

On the other hand, former Police Chief Adams was ultimately impressed with the festival and concert goers, supporting the event despite criticism. He claimed that he would “trust those people with their lives,” speaking of the festival attendees. Adams also commended them for opening the eyes of people who had long feared the prospect of counterculture.

Whether the Texas International Pop Festival was a success or failure, it left a tie-dyed mark on state and county history, despite dwelling in the shadows of Woodstock. Today, the Dallas International Motor Speedway no longer stands and the remnants of the festival site are long gone. Presently, the land is occupied by apartments, shops, and a DART Light Rail. Though the site may be gone, the memory lives on. Today, a historical marker commemorates Lewisville’s flower child weekend at the front of the train station. Not only is it remembered by a historical marker, but it remains in the hearts of hippies across the Lone Star State.

Damn! We just missed it. We should have been fall graduates!!

LikeLike