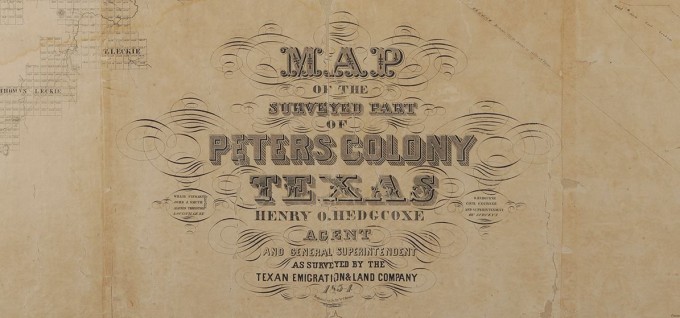

What once started as a small, farming community has grown into a residential suburban area located on the shores of Grapevine Lake. The city of Flower Mound is the subject of this week’s blog, with a heritage that begins in the early 1840’s.

Flower Mound is located in south central Denton County, an area inhabited by Wichita Indians before pioneers from the Peters Colony came in search of farmland. The settlers were attracted by the soil, which was perfect for growing cotton, corn, and wheat.

Beulah May Russell stands by her corn on a farm off of Morriss Road, 1930 (Images of America: Flower Mound).

The area was named “Flower Mound” for the fifty-foot-tall mound that peeked out above the surrounding Blackland Prairie. The mound bloomed with Indian Paintbrushes and wildflowers every spring, as it still does today. According to the stories, no structures have ever been built on the mound, and no tree has ever grown there.

Early settlers to Flower Mound were determined that their children would have a good education. For many, churches also served as schools during the week. Chinn Chapel was highly attended by the Flower Mound community, though it was not located in Flower Mound. Over time, quite a few schools populated the area, including: Bethel, Lane, Annie Blanton, Double Oak, Donald, and Hilliard schools.

Three students stand on the steps of Donald School in Flower Mound (Images of America: Flower Mound).

Out of those, only Donald School and Hilliard School were located in Flower Mound. Donald School was launched in 1880, located west of Long Prairie Road and south of FM 1171. After Donald School opened, the student population was split and attendance declined at Hilliard School. It closed its doors in 1903.

Donald School, on the other hand, served the community for several more decades. It was a two story building; elementary students were taught on the lower floor, and upper grades attended on the second floor. A wooden bus, driven by Frank Crawford, took the children to school every day. The school closed in the 1940’s when the student population became part of the Lewisville Independent School District.

Students pose in front of the Donald School’s wooden school bus (Images of America: Flower Mound)

Flower Mound grew steadily through the 1900’s, and became a substantial farming and cattle-raising community. With no bustling town center, many residents made the trip to Lewisville to buy groceries. Eventually, a general merchandise store called Yoakley’s opened in Flower Mound. J.R. Yoakley sold dry goods, hardware, groceries, and more from his storefront, and ran a peddle wagon throughout town for many years. Yoakley’s Store provided locals with a cotton gin, blacksmith shop and post office.

A painting of the old Yoakley Store (Images of America: Flower Mound).

Another community landmark, Gordon Grasty Barn was built in 1938 near the border of Flower Mound. Originally a dairy farm, a runway was built next to the barn in 1948 for a flight school. Every year, Flower Mound children gathered on the runway to hunt for Easter eggs. Whoever found the ‘prize egg’ won a free airplane ride. The barn was moved to Sweety and Alton Bowman’s property in 1984.

Wiley’s Dude Ranch was an entertainment hub for Flower Mound residents and surrounding communities. Located on the southeast corner of Morriss Road and FM 3040, the dude ranch was operated by Margarete and Paul Wiley. Visitors could stay the weekend and go riding and swimming. On Saturday nights, the ranch would host dancing and live music.

An advertisement for Wiley’s Dude Ranch (Images of America: Flower Mound).

In 1952, the United States Corps of Engineers began the construction of Grapevine Lake. It was completed a year later, and became a major recreational area in the community. The lake also stimulated Flower Mound’s economy as it attracted more residents.

Though it was growing, Flower Mound was still a small community. To avoid being annexed to the City of Irving, the Town of Flower Mound incorporated on February 27, 1961. Bob Rheudasil became the first mayor.

Ernest Hilliard and Johnnie Bays standing in what is now the bottom of Grapevine Lake (Images of America: Flower Mound).

In 1968, Flower Mound was chosen as one of thirteen communities to be part of the New Communities Act. This provided developers Raymond D. Nasher and Edward S. Marcus with $18 million in federal loans to set up four village centers and neighborhoods on the north shore of Grapevine Lake. This included schools, parks, and shopping and recreational facilities.

By 1970, Flower Mound had a population of 1,685. Construction on the new town began in 1972, but federal red tape, economic recession, slow land sales, and changing federal policy were causing the project to fail. By 1976, other new towns were failing too, and the project closed. The development, which had 300 people and 100 homes by that time, was renamed Timber Creek Community.

In 1980, Flower Mound’s population had grown to 4,402. A year later, Marcus High School opened on Morriss Road. This was the town’s first high school, named after Edward S. Marcus. The first principal was Larry Sigler.

From there, libraries, park, schools, and more sprang up across Flower Mound. The community experienced rapid growth, with a population of 50,702 by 2000. The once rural town had become a bustling suburb. Today, Flower Mound takes pride in being a family-oriented community with dynamic economic growth.

Flower Mound city limits sign (Images of America: Flower Mound)

All information in this blog was pulled from the Office of History and Culture’s archives, along with the books Images of America: Flower Mound by Jimmy Ruth Hilliard Martin and Sweet Flower Mound Land by the Flower Mound Historical Commission.